This article is the third in a five-article series on injury prevention based on anatomy workshops I teach. Due to the fact that we learn through repetition and shock (I am a big fan of teaching/learning through repetition VS learning through the experience of injurious shock), I would love to take a moment to recap the first two steps in my five-step process for injury prevention and longevity both on and off-the-mat: BREATH and BANDHAS.

Step 1: The Breath

To greatly reduce your risk of injury it is imperative to learn how the breath moves through the body and respond accordingly to this natural movement. There are 5 ways Prana – life force energy – courses through the body. These five winds (Vayus) have inherent qualities: upward, downward, expansive, contractive and pervasive (circulatory). In order to be in sync with the natural rhythms of Prana and move with ease and grace – and thus prevent injury – we want to reach UP on an inhale and DOWN on an exhale, we step or shift FORWARD on an inhale and draw BACK on an exhale, we want to EXPAND and OPEN our chest and limbs on an inhale and FOLD and CURL INWARDS towards midline on an exhale.

It is in stillness that we can connect to the continuous and miraculous swirling of energy within. Creating shapes both on and off the mat inspired and initiated by breath pretty much guarantees that we are moving upon this earth with grace and ease.

Step 2: The Bandhas

If we then layer the practice of activating, engaging, and strengthening our Mula (root) and Uddiyana (flying upward) bandhas (internal locks) on top of the unifying flow of body-mind-breath we will also find ourselves to be lighter, more lifted on this earth. Remember, gravity wants to pull us down…we, as yogi superheroes, want to engage and lift upwards in order to defy gravity! Being lighter on our joints will always aide in the quest for an injury-free life.

The third step to an injury-free yoga practice is bone alignment: an understanding of the skeleton and the movements of the joints and how we can move intelligently and safely with this knowledge. This is what we’ll cover in this article.

Step 3: Bone alignment

Have you ever been lying on your couch watching television or lying on your bed reading a book when all of a sudden you look up and you see your arm is in the air? I always find myself surprised when this happens and wondering “How long has my arm been floating weightlessly up there unnoticed?” The weightlessness and the ease that you experience while holding your arm up in the air (or when practicing Viparita Karani/ Legs up the Wall Pose) are due to the fact that you are practicing the art and science of bone stacking. One of the most immediate results of bone stacking is that almost no unnecessary muscle energy needs to be used and therefore poses are held with incredible ease. Ah…the sweetness of experiencing fully Patanjali’s Sthira Sukham Asanam.

Human skeleton: know and love thy bones

The human skeleton consists of 206 bones and is comprised of:

– the axial skeleton: made up of the cranium (skull), 33 bones of the spine, sternum (breast bone) and 12 pairs of ribs. And

– the appendicular skeleton: the shoulder girdle, pelvic girdle and limbs and extremities of each of these.

There are six major functions that the skeleton is responsible for;

- support – providing framework/shape

- movement – via the joints

- protection – of the internal organs and systems

- production of blood cells – via bone marrow

- storage of minerals (calcium and iron) and

- endocrine regulation – osteocalcin for blood sugar regulation

Bones are living tissue and respond to the healthy stress of weight bearing and adequate compression. Therefore it is important to move them and place them in certain ways that allow them to remain strong, supple and healthy so they can continue to effectively perform their necessary functions.

Bones are living tissue and respond to the healthy stress of weight bearing and adequate compression. Therefore it is important to move them and place them in ways that allow them to remain strong, supple and healthy.

The skeletal system is fascinating when you think of the shapes these bones can be arranged in. At the bone level we are essentially an axis with a bunch of levers and fulcrums…both a mathematician’s and an engineer’s dream! Even though muscles are so important in helping us to get in and out of all our desired shapes it is the bones themselves, their intimate relationships with their fellow bones in the body and both their abilities and limitations according to proportion and orientation that has always piqued my interest.

Working with, not against, your skeleton

I firmly believe that if yoga practitioners had a working knowledge of how the human skeleton was designed to move, there would be a lower rate of both on and off the mat injuries. Here are a couple of examples…

Backbends

In the Axial skeleton the lordotic curves of the cervical vertebrae and lumbar vertebrae mirror each other. So if you drop your head back in backbends like Cobra, Upward Facing DogandCrescent Moon Lunge most likely you are dumping in your lower back as well, thereby compressing and causing tension, discomfort, pain and/or injury.

- Read more about these curves and the anatomy of the spine

Twists

Vertebral joints in the spine are not designed to have a great amount of rotation. So in twists such as Ardha Matsyendrasana or Parivrrta Trikonasana keeping the ilium and sacrum (see image) anchored to the floor, rather than allowing movement with the “twist” of the spine (actually the turning of the torso) increases the risk of injury to the bones of the spine, the discs in between the vertebrae and the ligaments that connect the vertebrae. In addition, there is the unnecessary risk of injury to the sacroiliac joint if the sacrum chooses to follow the movement of the spine rather than stay connected to the ilium.

The joints of the appendicular skeleton

Ball and socket joints have a different range of motion than a hinge and a hinge has a different range of motion than a compressive joint. Trying to force the body into shapes that are beyond the scope of the bones, their ligaments and their range of motion can sometimes result in injuries that are irreversible. Knees and elbows are meant to hinge (flex and extend) and hinge only. The lower leg bones only rotate if they are bent (as in Virasana / Hero’s Pose) and for some people this will be much, much less than others, if at all. In poses such as Eka Pada Raja Kapotasana / Pigeon Pose the position of the lower leg depends on the range of motion and orientation in the hip – the femur bone in the acetabulum (socket) of the ilium. If the range of motion in the hip is limited, trying to get lower leg bones parallel to the front of the mat will force the knee. Ligament, tendon and other soft tissue damage will surely be the result.

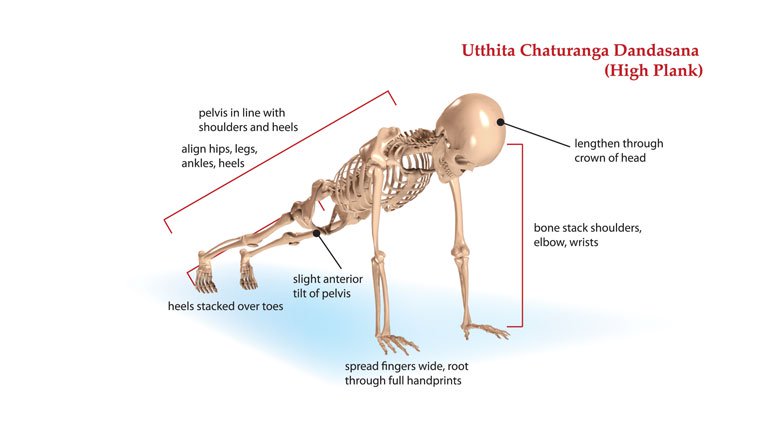

In the shoulder, the acromioclavicular AC joint – where the acromion (“roof”) of the scapula attaches to the clavicle – is a joint that commonly develops osteoarthritis in middle age adults from the normal wear and tear of aging. In Chaturanga Dandasana, one of the most commonly practiced poses in Vinyasa Flow Yoga, improper bone alignment of shoulder and elbow leads to harmful load/ weight bearing on this AC joint causing painful tendonitis and/or separation of the AC joint through the repetitive stretching of ligaments.

- For more on safe alignment in Chaturanga read For the love of the shoulder

Bone alignment in Plank Pose, Illustration by Suzanne Martin

These are just a few facts about the human skeleton that, if unknown, ignored and/or abused can lead to repetitive motion or traumatic injury. Although the human skeleton can bend and straighten and turn itself into so many impressive and admirable postures, unfortunately, if bones are twisted and turned into positions that are not supported by the actions of the individual’s joints, then damage can occur to not only the soft tissue in and around the joint (ligaments, tendons, bursts, meniscus) but also the bones themselves. Bones are connected to bones by ligaments, and ligaments – due to the fact that they are not elastic – will never go back to their original shape once stretched.

Know your own skeleton

Admittedly, I am an anatomy geek. I find myself so enthralled with the bones of the human body that there are days I find myself walking around, dropping my awareness deep into my body so I can experience myself operating at the bone level, repeating in my head, “I am a skeleton, I am a skeleton, I am a skeleton”. My bones and joints have a slightly different proportion and/or orientation than yours and it’s important to get to know our own bodies to move them safely. There are spaces in my body where I have great range of movement and yoga postures allow me to explore and delight in this. There are also areas of my body where proportion and orientation limit me in many poses. For example my hip sockets are set more forward than to the sides preventing deep external rotation and abduction.Take a look at some photos of different hip sockets.

With a working knowledge of my bones, general joint movement, my own individual range of motion (before, during and after yoga practice), and an incredible amount of respect for ligaments I know my risk of injury, both on- and off-the-mat, is lowered significantly. I want to practice yoga (especially vinyasa flow yoga) for the rest of my life…I would love if you joined me.

In the next part of this series we will explore how muscle activity enhances the support of our bodies’ health and longevity both on and off the mat.

Read all the articles in Jennilee’s series on preventing yoga injuries:

Illustrations are by Suzanne Martin and taken from Jennilee and Suzanne’s book The Perfect Chaturanga