Knee injuries – the figures

Almost every student I have ever taught has complained about some sort of knee pain, knee injury and/or knee surgery. The more I research knee injuries the more the numbers astound me. According to the Consumer Product Safety Commission an estimated 6,664,324 knee injuries were presented to US emergency rooms from 1999 to 2008. And that is only half the amount that made it to doctor’s offices in the year 2006 alone (National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey reported 12 million visits!) The American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons reported that in 2010 there were 10.4 million visits to doctors’ offices because of common knee injuries such as fractures, dislocations, sprains, and ligament tears. Between 1991 and 2007 the rate of knee replacement in the US alone rose a dramatic 187% whereas hip replacements rose 86%.

Why so many knee injuries?

In order to understand why there are so many micro-traumatic and traumatic knee injuries we must first understand the construction and limitations of the knee.

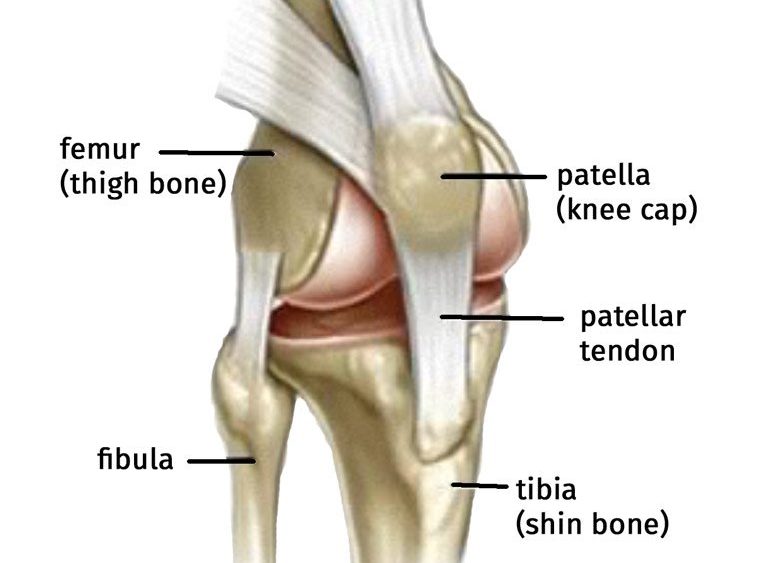

Anatomy of the knee

The knee joint is made up of three bones: Femur (upper leg and the longest bone in the body), Tibia (medial lower leg bone – your “shin”) and the Patella (kneecap which is a sesamoid bone embedded in the quadriceps tendon that inserts below the knee at the tibia). There are four ligaments that stabilize your knee joint: Anterior & Posterior Cruciate Ligaments and Medial & Lateral Collateral ligaments. There is also a cartilaginous cushion called the meniscus inside the knee joint.

The knee joint is a hinge joint which means its job is to flex and extend in the sagittal plane. There is minor internal and external rotation of the lower leg bones in some people when the knee is in a flexed state. In many yoga poses, if we are not aware of our knee’s limitations (for example: hyper-extension, hyper-flexion, patella not tracking correctly, medial or lateral injury, and/or tears, sprains or inflammation due to these four) and how to align accordingly (for example: bone stacking, knee tracking, hip rotating vs knee rotating, no collapsing into arch and /or inner leg) we often risk over stretching and/or tearing ligaments, tearing meniscus or compounding the pain that is present due to one of these or by the wear and tear of aging (osteoarthritis) .

As we go further it is important to remember that ligaments are not elastic and once overstretched will never go back to their original state.

Most common knee injuries:

In addition to osteoarthritis (degeneration of the cartilage of the knee through the wear and tear of aging) the most common knee injuries that I witness are from micro trauma (habitual repetitive motion patterning) and/or from trauma – many from sports, dog or automobile related accidents.

1. Tear of the Meniscus:

Inside the knee joint there are two little half moon shaped cushions of cartilage called the menisci (medial meniscus and lateral meniscus). They help in shock absorption and in balancing the weight across your knee. When people talk about torn cartilage in their knee they are mostly talking about a meniscus tear. Tears to the meniscus often occur when the knee is twisted, especially when the foot is planted. People with meniscus tears often find classical Virabhadrasana (with foot rooted at a 45 degree angle) uncomfortable and/or painful (the anchoring of back foot and a turn at the knee versus the hip). Severe meniscus tears can move into the joint space and often cause locking of the knee joint. Whether minor or severe, meniscus tears cause pain and swelling.

2. Tear of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament:

Your ACL is largely responsible for the stability of your knee. It originates deep in the notch of the distal femur (more towards the back/posterior portion) and attaches to the front (anterior) portion of the proximal tibia and prevents the tibia of slipping forward of the femur. A tear in this ligament or over stretching this ligament often results in the knee “giving out” towards the back. Hyper extenders at the knee tend to over stretch this ligament (and ligament once stretched will never return to their original shape/length).

I myself suffer from this (or the PCL) ligament being overstretched…especially after practicing a system of yoga that encourages (almost forces the point) “locking the knee” in one legged balancing poses such as Natarajasana, rather than pressing through the four corners of the foot and engaging the quadriceps to support the extension of the knee vs. the dumping/falling/collapsing into the back of the knee.

Other than over-stretching this ligament, most traumatic injuries (tearing) are incurred by changing directions rapidly while running or landing incorrectly with misalignment at and/or a straightening of the knee joint. This injury is usually accompanied by a “pop”, swelling after a couple of hours and pain when flexing. Often surgery is needed to repair an ACL tear.

3. Tear of the Posterior Cruciate Ligament:

Your PCL is the strongest ligament in the knee and an injury to this ligament occurs much less than to the ACL. Your PCL extends from the back (posterior) portion of the proximal tibia to the front (anterior) portion of the distal femur and prevents the tibia from moving posterior beyond the femur bone. Common traumatic injuries to this ligament direct blows to the flexed knee (car accidents are the common reasons for injuries to this ligament) and also landing improperly on a misaligned and/or straightened knee joint after jumping. This ligament is also over-stretched with those of us that hyper-extend at the knee joint (especially during weight bearing one legged balancing poses). Some who have tor their PCL have heard a “pop” much like when you tear the ACL, others heard no “pop”.

4. Tear of the Medial Collateral Ligament:

The MCL attaches from the medial distal femur to the medial proximal tibia. Its primary job is to stabilize the knee and avoid lateral movement of either the femur or tibia. When stretched or torn, damage to the medial meniscus is most often the case (the lateral meniscus is not attached to the lateral collateral ligament and therefore injured 50% less than the medial meniscus). Traumatic injury of this ligament is due to excessive force being applied to the straight knee from the outer leg in. Many a Medial Collateral Ligament has been traumatically injured at a dog park or on a football field.

*As a yogic side note, please do not place your foot against the medial knee in Vrksasana or Tree pose…this can damage the Lateral Collateral Ligament which attaches from the lateral distal femur to the lateral proximal tibia.

Honoring our knees in yoga postures

To ensure knee joint stability be continuously aware and vigilant of these three things:

- the geometry and alignment of your femur, tibia and patella bones.

- the cruciate & collateral ligaments and the meniscus

- muscles that support the knee joints movement

Let’s take a look at how you can avoid hyper-flexion, hyper-extension and injurious rotations of the knee in the following poses….

Avoiding hyper-flexion in Virabhadrasana – Warrior poses

The safest place for your knee in Warrior 1 & 2 poses is stacked directly over the heel and in line with the second toe.

If your knee extends beyond the ankle and heel there will be unnecessary force and pressure on the Patella Tendon and on the Posterior Cruciate Ligament as the femur shifts beyond the tibia. If the knee knocks in towards the big toe there will be too much pressure on the Medial Collateral Ligament and the Medial Meniscus. If the knee heads too much over towards the little toe then the Lateral Collateral Ligament will feel the strain. This same bone stacking on knee over ankle/heel needs to be safely performed also in openhearted warrior, humble warrior, reverse/exalted warrior, warrior one with a lunge and side angle pose.

*It Is also important to note that damage to the Medial Collateral Ligament and the Medial Meniscus can occur if one collapses into the arch of the back foot and the back knee in any of these poses.

Avoiding hyper-extension in Utthita Trikonasana – Triangle Pose

In extended triangle pose where both legs are straight it is common (especially for those of us that hyper-extend at the knee joint) to collapse in the posterior knee. To ensure the health and longevity of your anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (and therefore the stability of your knee joint) it is important to root through the four corners of both feet, engage the four muscles on the front of your thigh (quadriceps), and lift the knee cap to support extension at the knee without hyper-extending. Also, make sure to not roll to the inner or outer foot (rooting through four corners is best) as this will put too much strain on the Medial and/or Lateral Collateral ligaments and possibly the menisci.

Avoiding injurious rotation

It is important to know that the degree of rotation of the lower leg bones at the flexed knee joint is quite small. Some people have a little bit more than others but really, rotation is not the desired movement at the hinge joint of the knee. Often students experience discomfort, pain and possible injury in poses such as Eagle, Hero or One-Legged Pigeon due to the fact that even though these poses ask for adduction, internal or external rotation of the femur in the hip socket most people end up, due to lack of range of motion in the hip or compression of bones or soft tissue in or around the hip, forcing the lower leg to make up the difference to get into the “fullest” version of the pose.

Eagle pose – Garudasana

In Eagle pose we often try to make up for our inability to adduct the femur by rotating the lower leg bones while wrapping to get the foot around the ankle.

Hero pose – Virasana

In Hero we often try to make up for our inability to internally rotate our femur in the hips socket by over internally rotating the lower legs bones.

Both of these actions in these two poses apply too much force and pressure on the Medial Collateral Ligament and Medial Meniscus.

One-Legged Pigeon Pose – Eka Pada Kapotasana

In One-Legged Pigeon we often try to make up for our inability to externally rotate the femur in the hip socket by over external rotating the lower leg bones (especially to reach the “fullest expression” of the pose where lower leg is parallel to the front edge of mat… unattainable for many of us with minimum external rotation at hip). This puts unnecessary force and pressure on the Lateral Collateral ligament and the menisci.

But, born with the knees that we have, it is important to love, honour and respect them for all their limitations, as well as all their potentialities.

Loving Our Knees

The knee seems to have been designed more for the running away from lions, tiger and bears and less for the rotation and compression we continuously ask of it. It being such a lower center of gravity joint you would think it would have more cushion as well as wider and stronger ligaments.

As with every yoga pose, and transitions in and out of them, general human anatomical knowledge and an intimate awareness of our personal bodies aid in our physical and mental longevity…both on and off the mat.

Other articles you may enjoy: